What do we remember? The blur of objects, a yellow bird, a clown, polka dots, the dead owl, a monkey, the plaid shirt, stripes, colors, a wall of inflamed sayings, marbles on the floor, thousands of nails mapping fragile bodies of water. We remembered how we felt as we looked, up high, down low, somewhere in the middle. We considered how little we look, at each other, at everything else, when we are together, learning. We remembered the shapes of objects, ideas, our bodies moving, in the classroom, in the galleries. We remembered what it feels like to keep something we know or have experienced, with us.

While looking at art, talking about it, we remembered because memory is held in places we did not expect: on the edge of our wrists, in between the flaps of our journals, inside the folds of our pockets, at the tip of our tongues. The art seemed to help us remember things. Concrete and abstract things: colors, shapes, sounds, words, joy, anxiety, dismay, hope. Somewhere in our minds, eyes, limbs, in the open air, in the volume of the room, we were all holding on to things that we were learning as they collided with things that we already knew.

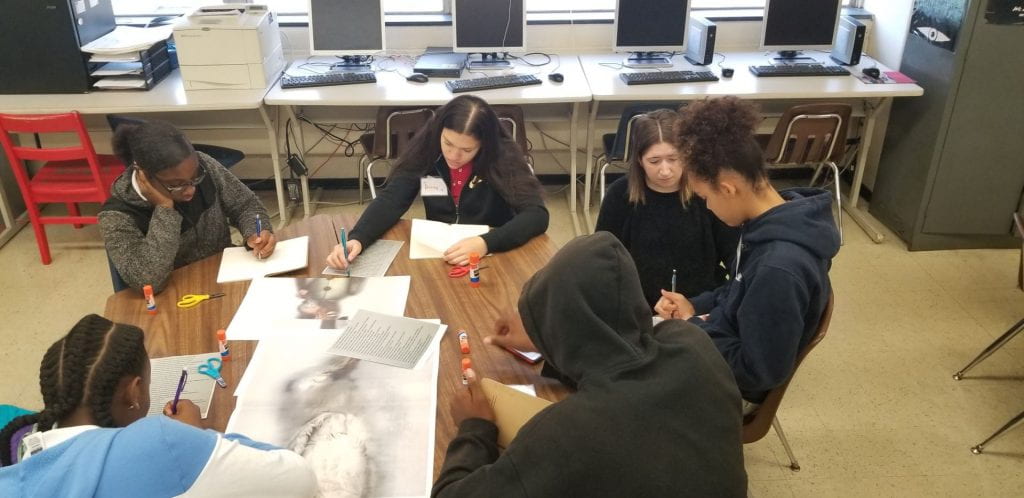

Students in the classroom working with artist-in-residence Michelle Sipes; using Ann Hamilton’s artwork as a text.

While out in the classrooms and at the Wex, by the look on students’ faces, many had not considered we could learn like this: standing up, crouched down, rearranged, on the floor in an art gallery, up close to a wall of words, underneath the sound of whistling drifting from the record player; in front of clusters of nails precisely placed and shaped like a body of water protruding from the wall; surrounded by thousands of marbles gathered and spilling as waterway, as river, as bloat, as flood.

How do we grasp these somewhat intangible things? How do we make a space to hold them alongside other notions in our minds that come and go? Where do we put the ideas, concepts, that we are not required to learn for school, for a test? How do we know what to keep and let go? When we are learning with art, we practice giving ourselves permission to get comfortable with learning to think, remember, as tools for life, instead of memory as a short-term transactional response.

A New York Times article by Dr. Perri Klass, talks about the relationship of arts education and memory; highlighting the work of Dr. Mariale Hardiman, a professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Education. Hardiman does research about learning and retention. Hardiman, a former school principal, now does research with children and memory, where she looks at how the arts play a vital role in the working memories and information retention of K-12 learners.

In Hardiman’s article “The Effects of Arts Integration on Long-Term Retention of Academic Content,” she maintains that the arts and arts-integrated learning, allows students to think about information in new ways which seems to support retention of what is learned.

Thinking back to our visual arts pre and post visits in the classroom; when Pages artist-in-residence Michelle Sipes, encouraged us to use our whole bodies to look. We noticed where the sunlight hit the spaces in the room. When we looked longer; we found the deep scratches, thin stray lines jagged and crisscrossed on the wooden tables. When we looked high and low, we noticed how narrow we keep our pathways. How small we keep ourselves. How we rarely practice noticing things. In the visual arts classroom, with art educator Mindy Staley, and her students from Whitehall-Yearling high school, we opened up about how we can move our bodies to look, to notice things around us in new ways. We trusted how our muscles knew what to do. How looking, moving, longer, opened up our pathways to capture some things old and new.

In the galleries during the exhibition Here: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin, with English/Language Arts educator Enddy Stevens, and her students from Walnut Ridge high school, we discovered a dozen ways to name Ann Hamilton’s piece when an object reaches for your hand – shaped stone. The work is a photograph draped ceiling to floor, of a circular object, a Pre-Roman artifact. “What is this?” a student asked. The question was followed by a collage of ideas rattled off by her peers. Maybe it’s a prehistoric tool, a burnt bagel, a spectacular silver bell, a broken wheel, time. One student said it reminded her of her grandmother. While we looked and listened to each other, students did not self-censor due to fear or embarrassment. Instead, they dug into themselves to think, to unearth things lingering in the backs of their minds. They did not overly consume themselves with getting the right answer. Instead, these students remembered what they already knew, deep down underneath the rigors, rules, and repetition of thinking and learning. However, it was that time and space in the galleries; that invited learners to take notice of their own imaginative ideas. Realize those ideas had meaning, and could elicit surprising connections that were worth thinking about and keeping.

-Dionne Custer Edwards