The arrival of  Bryan Moss, an amazing resident artist with the PAGES Program, in my classroom made me think of an article I read years ago about James Thurber. Thurber, who became known for his humorous short stories, was rumored to doodle little comics to clear his head before writing. He promptly threw the doodles away, thinking little of them. E.B. White shared an office with Thurber and, finding the sketches, submitted them for publication at The New Yorker where the two worked together at the time. Thurber’s sketches proved to have just as much to say as his written works.

Bryan Moss, an amazing resident artist with the PAGES Program, in my classroom made me think of an article I read years ago about James Thurber. Thurber, who became known for his humorous short stories, was rumored to doodle little comics to clear his head before writing. He promptly threw the doodles away, thinking little of them. E.B. White shared an office with Thurber and, finding the sketches, submitted them for publication at The New Yorker where the two worked together at the time. Thurber’s sketches proved to have just as much to say as his written works.

I love this story about Thurber because it reminds me as a teacher of the different forms thinking manifests itself in. I love Bryan Moss for sharing his creativity and freedom of expression to guide me and my students beyond typing another essay. As honors 10 students, they take comfort in following the same formulaic structure; they pride themselves on nearly mastering it for the benefit of passing standardized tests, maintaining GPAs, and my fear, pleasing their teachers. While students proving their mastery on an end of the course test and vying for valedictorian are realities, we cannot lose sight of providing students with a safe place where expressing themselves in a unique, individual way is encouraged and celebrated. Obviously, students are not standardized. And, I hate to think that my class played any part in making students lose sight of the beauty and power of their own words. With Bryan, we sought spontaneity and individuality over a robotic prompt.

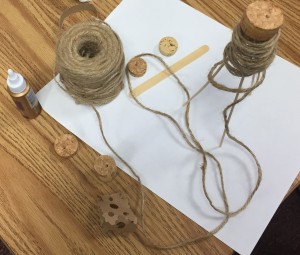

So, what did we do to merge what students were accustomed to writing with a fresh approach? By inviting Bryan into the classroom, we invited colored pencils, crayons, markers, glue, wine corks, construction paper, scissors, tin foil, painted rocks, feathers, and pipe cleaners into the classroom,too一the high school classroom. With this smorgasbord of items, we asked students to create something that represented themselves. Students were at first hesitant, but then they seemed to channel some form of their younger selves when they were less concerned with being right and more concerned with making something.

Once students completed their work, Bryan scrambled them so that each student moved to a desk with another classmate’s artwork and journal on it. Students wrote in their peer’s journal about what they saw in the piece before sharing their interpre tations with the whole class. Then, the student artist was given a chance to respond to the interpretation presented. This worked brilliantly as student critics brought power and meaning to a piece that the original artist may have been too shy, humble, or subconsciously unaware of to own. Student critics also encouraged the creator to rethink his or her choices; was the piece really saying what they thought it would or should? This reflection prompted a new way of viewing the possibilities in their writing as well as their reading of other’s work. There was also beauty in receiving feedback in real time on the spot from their peers because, as a class, we established group permission and support in taking creative risks both with what we find in a piece as well as how we develop our own ideas.

tations with the whole class. Then, the student artist was given a chance to respond to the interpretation presented. This worked brilliantly as student critics brought power and meaning to a piece that the original artist may have been too shy, humble, or subconsciously unaware of to own. Student critics also encouraged the creator to rethink his or her choices; was the piece really saying what they thought it would or should? This reflection prompted a new way of viewing the possibilities in their writing as well as their reading of other’s work. There was also beauty in receiving feedback in real time on the spot from their peers because, as a class, we established group permission and support in taking creative risks both with what we find in a piece as well as how we develop our own ideas.

And here’s the twist, the critical thinking generated by nudging students (and their teachers) outside of our comfort zones only enhanced those essays we later tackled because students felt free to experiment with the what and the how of their topics. James Thurber and Bryan Moss remind us that doodles and creative pieces have just as much to say, and prove just as much a challenge,  as those 5-paragraph essays; critical thinking doesn’t need to be three pages, double-spaced, and in 12 point font. Sometimes the best place to begin is with some twine, a glue stick, and a painted rock.

as those 5-paragraph essays; critical thinking doesn’t need to be three pages, double-spaced, and in 12 point font. Sometimes the best place to begin is with some twine, a glue stick, and a painted rock.