We will screen Girlhood, a film by Céline Sciamma, in a matter of days, and we are busy in the classroom engaging with this upcoming experience in myriad ways. When encountering a text, or a large body of work in Pages, we try to avoid considering that text as the end all, be all, the grand moment, the point to reach, and then we’re done. Instead we cultivate conversations between the main text and other texts, sometimes, unlikely ones or weird ones; we stretch and stretch some more, the content and themes. We ask: How many different ways can we get into this work, and make connections beyond it? Below are some examples:

What’s in a name? –with Kim Leddy, Mosaic

Mosaic students are beginning a big folklore project, and with that we began to think about the narratives of our lives. We considered these tales that wave and warn our curiosities into wonder and at other times into submission.

We began with the folklore of names, entertaining why we name things, especially inanimate objects, and that led us into two nonfiction texts, excerpts of text-based journalism, about the folklore around how Apple’s iconic Siri got her name. We read two excerpted versions of the story (tech folklore if you will), then had students turn to writing their own coming-to-name narratives, a play on the idea of coming-of-age, a central theme in the film, Girlhood.

Whose life is this anyway? – with Kim Swensen, Westerville North

Students are in the thick of Toni Morrison’s Sula, so we paired that text with the children’s book, also by Morrison along with her son Slade, The Big Box, and a song in the front yard, by Gwendolyn Brooks. In those pairings we discussed identity, boundaries, oppression, and choice. Students found the characters in each of the text were seeking something, but in that seeking there were obstacles, interventions, and consequences.

After a rich discussion making connections in all three texts, students wrote in the voice of the character in the Gwendolyn Brooks piece, seeking beyond what is immediately before in plain sight. Students asked themselves what they were curious about, what spaces, boundaries, or mindset did they want to break open or expand, theme explored at length in Girlhood.

Why don’t students read more poetry? – with Thomas Hering, Delaware Hayes

Students are reading The Yellow Wallpaper, and thinking about ideals around feminism, oppression, and voice. We wanted to explore more poetry (because students do not get a lot poetry in the curriculum), so we paired that short story text with a few poems, one we read in the pre-visit, Letter to a Friend Unsent, by Rebecca Lindenberg. We also began with a short video clip of Naomi Shihab Nye on the civic responsibility of the poet, a case for poetry to move and stir the senses, a permission to be human and to feel emotion and vulnerability, to engage with empathy.

We pulled the texts in conversation with each other, as students made connections to safe and unsafe spaces, boundaries and oppression, the stillness or the coming to voice, something the main character in Girlhood grapples with throughout the film, and themes running through The Yellow Wallpaper.

What can we learn from the artist and why is that important to our writing? – with Aaron Sherman, ACPA

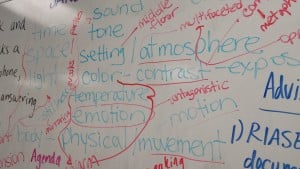

We used our session to slow down and learn from the artists, using two different texts: film and poetry. We wanted to explore time and space, and as the lesson developed had the chance to explore so much more than we anticipated. We watched a scene from the high suspense film Day Night Day Night, by Julia Loktev, then listened and read the poem The House with Only an Attic and a Basement, Kathryn Maris.

Watching the film we entertained three ideas: a question for the excerpted work, what information we could gather from the scene, and considerations of before and/or after [the scene}. The point was to take an extended, close look at the film and gather ideas on what the artist was doing to pull us through the narrative. Students identified uses of color, light, sound, long close-ups on the character, limited dialogue, and the placement or use of objects in the scene to create suspense, slow down or speed up time, tension, and to build the narrative.

After the film clip, we listened to a reading of the poem by both the author and a student in class. Listening to at least two different versions of the reading is an ideal entry to the poem. Following the readings, we used the same extended looking to peel away what the writer was doing in the work. In both cases with the film and the literature, we stayed away from meaning (it’s a good challenge for students), to examine the art and what the artist is doing to convey that meaning as practice for watching a film with subtitles: following the narrative as it unfolds, and looking for clues in the imagery and context, even as the dialogue flies across the screen (this practice especially essential for slower readers of text).

Often students get stuck in only knowing how to seek out meaning, analyze the text in a way that is tunneled and limited. In this exercise we create boundaries for students to slow down and look at the work, not just for meaning (though you can build that in later), but for technique, artistic devices, choices the artist is making. Students can become better writers by learning what a writer is doing in their work, not just what the work is saying or means (though that’s important too!).

In the end we wrote for a short time taking what we learned and trying to transfer that into the writing.

So you want to make a documentary? – with Andrea Patton, Whetstone HS

Students want to make coming-of-age documentaries. Again, the coming-of-age theme is central in the film Girlhood. However, as I’ve learned from a range of visual media artists, documentaries just don’t happen, in other words, you turn on a camera and just film. Documentaries need a premise, intention, and could use some pre-writing as a way to organize ideas, the stance, or the narrative.

We watched the documentary They Call Me Muslim Diana Ferrero, and gathered as much information as we could, forging the meaning or premise of the film (though that was tempting to many students), but rather what the filmmaker was doing to deliver or convey that meaning or premise. We considered that if they want to make documentaries, they should watch a few to learn to the craft.

With help, students did a nice job keeping their opinions of the subject matter of the film to themselves, and keeping a sharp focus on what the filmmaker did to highlight the varying points of view of the subject matter. It was important to not get burdened by whether or not we agreed or disagreed with the opposite stances of the film, but rather to consider whether or not those stances were in balance. We watched the film to learn from the filmmaker and what she did or did not do in conveying the perspectives and subject matter, resisting chiming in with our opinions on said subject matter (there will be plenty of time to debate that later).

Mastering the Argument – with Elise Allen, Central Crossing

Students will inevitably have to write persuasive pieces, argument essays, works that try to convey a notion to the reader. But before students can do that they need to know who that reader is, make a few assumptions, and then on to the persuasion of said reader. However, if students never learn to write to, or at the very least consider their reader or audience beyond just the teacher grading the essay, students will get stuck repeating the same ideas over and over again without bringing in any evidence or fact to support the stance. We encouraged students to think beyond just writing to the teacher. Who is your audience, and how will you convey your stance to that audience? If the only assumption is your audience is your teacher; that limits the risks a writer will take to convey an idea or stance.

We watched a short documentary film, They Call Me Muslim, by Diana Ferrero. The film explores two sides of an issue, and students, while watching (with subtitles – more practice for the film Girlhood), gathered information. What is the thesis or stance? Who is making the case? How is the filmmaker making that case? Who is the audience? Watching an argument reveal itself on screen, allows students to see how an artist can “show and tell”. It also allows students to have a critical eye for bias, something that will help students curb bias in their own writing.

In the end, we explored the visual argument as practice for text-based argument writing. The documentary is a good resource for exploring how-to tackle persuasion.

All the World’s a Stage (and we wonder what it sounds like) – with Laura Garber and Sarah Patterson

With Shakespeare in our pocket and Girlhood on our mind, we explored coming-of-age in a slightly different medium – music. After viewing and listening to the BBC’s beautiful visual mash-up, BBC a lifetime of original drama, of the text All the World’s a Stage, by William Shakespeare, we annotated ideas and discussed our ideas about the themes of the piece and looked to understand the seven stages both literally and figuratively.

Students then took to creating their own seven stages, interpreting the premise of that text using musical selections to represent their understanding of each of the seven stages. Students will also do some research on coming-of-age in France, grounding them with cultural context for the film. But the pre-visit, inspired by the Shakespeare piece, enabled students to not just read the piece, but create their own stages of lyrics and sound, an engaging way to explore the text and relate to it in the contemporary. Check out the Pages Twitter feed, @pagesprogram, to see examples of songs from students’ playlists.

-Dionne Custer Edwards